By Marco Avolio

![]()

| Contents |

| 1.0 Acknowledgements |

I wish to thank Mr. Abe and the congregation of Montreal Buddhist Church for kindly welcoming me into their community and their willingness to participate in my project. I would also like to thank my colleagues, Tom Troughton and Jonathan Gallant, as well as Professor Hori, for their help and insight.

| 2.0 Historical Introduction |

One cannot understand the Montreal Buddhist Church without first understanding the historical context and conditions it grew out of. The central challenges it faces today and its peculiarity as a North American Buddhist organization only begin to make sense in light of the history of the Japanese and Jodo Shinshu Buddhism in Canada and North America before World War II. For this reason my report begins just before the turn of the twentieth century. As the reader will notice, everything that follows is informed by the themes and concepts that begin in this necessary, if lengthy, historical introduction.

2.1 Nishi Hongwanji’s Expansion East

While the Meiji period (1868-1912) ushered a resurgence of traditional values and imperial rule in Japan, it was also a time of heightened interest in the modern western world. Two attitudes that arose in this context were key catalysts in Buddhism’s expansion to North America.

The first is the anti-Buddhist movement, the strongest manifestation of which was the then newly formed Department of Shinto’s Separation Edict that declared Buddhism to be “contrary to the ‘indigenous Japanese’ way of life” (Watada 16). Buddhist temples were taken down or reclaimed and priests were forced to lead a lay life or become Shinto priests.

The second is the heightened interest and encouragement to move to new countries. Many who left did so to be able to practice Buddhism freely, and so took it with them to new lands. When at the turn of the century Buddhism re-emerged as a popular religion, the “Hongwanji and other Buddhist groups…began philanthropic work in Hokkaido, Taiwan, Korea, South China and Manchuria” (Watada 21). Those who had moved away wanted the benefits and services provided by Japanese monasteries. In its exile Buddhism started to find new homes and communities to serve. Janet McLellan notes that around the turn of the twentieth century, the “Hongwanji branch of Jodo Shinshu was…the only Japanese religious tradition prepared to meet the spiritual needs of overseas Japanese. As early as 1880, then Abbot Myonyo created an overseas mission for Hongwanji members” (41).

2.2 The Hawaii Situation: Buddhism in Christian Clothing

Hawaii was the stepping-stone in Jodo Shinshu’s migration to North America (Hawaii was still an independent kingdom in 1889 when Soryu Kagahi, a Japanese Jodo Shinshu Priest, arrived there with Abbot Myonyo’s blessing). It was there that Buddhism first had to compete fiercely with Christianity even for Japanese followers who were originally Buddhist. By the 1920s, however, the Nishi Hongwanji alone “boasted a membership of at least seventy-five thousand” (Hunter 129). Combined with the popularity of other Buddhist sects, this disheartened Christian leaders, “who deplored the ‘repaganization of Hawaii’” (Ibid.).

Despite its growing popularity, Japanese Buddhist institutions eventually transformed in order to cater to younger generations who adopted more Westernized values and lifestyles—which were the values and lifestyles of a worldview that still saw Buddhism as primitive and un-American. Louise Hunter succinctly describes the situation:

The Friend reported at the turn of the century that the Hongwanji had even appropriated the terminology of Christianity and altogether ‘absorbed’ the forms of the Christian religion. Temples were called ‘churches’ by Buddhist laymen, and priests were frequently addressed as ‘Reverend’…the new Honpa Hongwanji betsuin (built in 1918) was reported to be the only Buddhist temple in the world to be equipped with a pipe organ and an indirect lighting system. (131)

This Christian clothing, as I have called it, is still present in Canadian Buddhist churches, and the MBC is no exception. The issue of Christianizing Jodo Shinshu will be discussed in more detail with reference to the MBC’s rituals and practices, as well as its doctrine. It is enough for now to say that it is characteristic of the perhaps paradoxical Japanese attitude of the time which was alluded to earlier: on the one hand there was an effort to preserve and strictly adhere to traditional values, while on the other a heightened interest in the Western world and its values.

I received mixed answers about the Japanese community’s feelings toward Canadian Jodo Shinshu’s Christian look. One member, for instance, said that it is not un-Buddhist, but a natural translation of terms, as though it is merely a difference of language. A Jodo Shinshu minister, on the other hand, said that the terminology is misleading and that there is an effort to use Buddhist terminology again. This seems to be true in western Canada, where most Jodo Shinshu institutions are called temples rather than churches. The Calgary Buddhist Temple also refers to clergy as sensei rather than ministers (http://www.calgary-buddhist.ab.ca).

2.3 Early Japanese Canadians and Canada’s First Buddhist Temple

Around the turn of the century, Japanese immigrants in British Columbia, as those in Hawaii, began to feel a great amount of pressure to convert to Christianity. Buddhism was not viewed through a romantic and idealistic lens as it is today, but was seen by many as more primitive and less progressive than Christianity. This was even true within the Japanese community: in 1896, the Japanese Methodist Church was founded in Vancouver by a Japanese reverend who thought that all Japanese should assimilate and convert. By the 1930s, the United Church claimed 4789 Japanese members. Many converted because of a change in faith, while others because of its connection to a western, Canadian identity. Most (68%), however, preferred Buddhism: “The Japanese in Canada…saw Buddhism as their one link to Japan and thus to their roots. Their religion was a tool in teaching their children obedience to the Emperor, the teacher, the parents, and the elder brother or sister” (Watada 29-30).

However, many issei parents (issei are Japanese Canadians born in Japan) saw the absence of a Buddhist institution as a barrier to the moral instruction of their children (nisei), and turned to Methodist and Anglican churches to deal with this problem. Some saw this as a move to assimilation, while “others did not see it as an abandonment of Buddhism but rather a pragmatic way of conveying moral values to the children….” In 1904 the Buddhist community were granted a kai kyoshi (a Jodo Shinshu priest) by the Nishi Hongwanji (Watada 36-37). Rev. Senju Sasaki and his wife arrived in October 1905 and started holding services in a hotel room in December. By his great efforts and the help of the Japanese community, Rev. Sasaki raised enough money to buy a piece of property in Vancouver that became the first Buddhist temple in Canada on November 9, 1906 (Watada 39, 41).

2.4 Racist Anxiety, National Consciousness and the Death of Emperor Meiji

While the Russo-Japanese war had no direct impact on Canada, Japanese-Canadians still suffered the effects of the anti-Japanese hysteria that spread through Europe because of it. In fact, in 1907 racism and anxiety about the “Yellow Peril” came to a head in a violent riot organized by the Asiatic Exclusion League in Vancouver’s “Little Tokyo.”

It was in the wake of this racism that Rev. Sasaki began to speak out about the need for the Japanese community to retain a strong national consciousness in order to not become entirely taken over by the West. At this time “the Buddhist Church became the centre of the community since it offered a refuge from the threat of white racists and a haven where common language existed and tradition was upheld” (Watada 42-45).

What this national consciousness became was dictated by two major factors: the decline of Japanese immigration to Canada and the death of the Emperor Meiji in 1912. The decline in immigration is due partly to the Immigration Act of 1910, which gave the Canadian “government enormous discretionary power to regulate immigration” (Dench). In context of the racism discussed above, this led to the curtailment of Japanese immigration, though because of an agreement with the Japanese government, its impact was not very significant. The decline is due mostly to the limits the Japanese government after Meiji imposed on immigration to Canada.

Terry Watada notes that beginning at this time, because of the situation discussed in the last paragraph, “the Japanese community was no longer under the influence of cultural and societal changes in Japan. A Japanese Canadian culture emerged steeped in the Meiji paradox,” discussed above, “of embracing Western technology while fiercely adhering to Japanese tradition” (52). The national consciousness cultivated by the community surrounding Canadian Buddhist churches up to and after World War II is characterized by this paradox.

2.5 Internment and Dispersion

After the bombing of Pearl Harbour Japanese Canadians were put in internment camps until the end of the war and Jodo Shinshu churches were prohibited from having gatherings of any sort, though ministers continued their regular practices. At the end of the war the BC government gave those who had been interned an ultimatum: either repatriate or move to another part of Canada. Many chose to move east, and Japanese communities were formed around Jodo Shinshu churches throughout Alberta, in Winnipeg, Thunder Bay, Hamilton, Toronto and Montreal.

2.6 Reorganization: the Role of Post-War Parent Administrators

In 1946 the churches reorganized, setting up the Canada Bukkyo Kukyo Zaidan, “an economic committee for the propagation of Buddhism in Canada,” which divided Canada into four jurisdictions: British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba and a jurisdiction made up of Ontario and Quebec. In the 1950s the Buddhist Churches of Canada was formed to administer the four jurisdictions and facilitate communication between the churches (McLellan 46). It still fulfils this role, as well as several others, including assigning ministers, helping arrange monetary aid for churches that need it and solving administrative disputes (Watada 261-262).

As well as serving to mediate between churches within Canada, the BCC mediates between those churches and the Nishi Hongwanji headquarters in Kyoto, which administers the BCC and other similar branch organizations, such as the Buddhist Churches of America. As it has from the time of the first overseas missions in 1880, the Nishi Hongwanji still retains the sole authority to certify all Jodo Shinshu ministers that come to Canada. There are two steps to becoming a minister: (1) one becomes a Buddhist monk in the Jodo Shinshu tradition, (2) one has to take courses and get a teacher’s certificate.

The first step can be taken in North America. Currently one must go to the Nishi Hongwanji headquarters in Kyoto to complete the second step and be fully ordained, but plans are being made to set up a training centre in Berkeley through which ministerial candidates in North America will be able to take the teacher’s certificate course in English by correspondence. However, even with this program, candidates will probably have to go to Kyoto to take a final seminar and apply for full certification. Neither the Nishi Hongwanji nor the BCC support ministers financially; that is up to the individual churches and their communities.

| 3.0 The Institution and its History |

3.1 The Founding and Early Years of the Montreal Buddhist Church

The Montreal Buddhist Church was founded in 1947 by issei and nisei who came to Montreal after living in the internment camps in British Columbia. Like other Jodo Shinshu churches in Canada, it served as the centre of the Japanese community that founded it (two other Japanese churches, one Catholic and one United, that served communities that came to Montreal after the war were also founded during this period), and maintain the national consciousness discussed above. The history of its community activities points to this.

Starting in the 1950s, the church began organizing and hosting bazaars, karaoke, bowling, Obon Odori dances, mochi tsuki, and kindergarten Sunday school. These are community activities which encourage close personal networking, bringing members of the church community closer together. Moreover, these activities are common to many of the Jodo Shinshu churches across Canada, linking them to a wider Japanese Canadian experience and identity. The ethnic and cultural identity cultivated by these activities is as important as and inextricably tied to the religious dimension of the church. Several nisei members told me that the church has been the focal point of the community; one even remarked that its members would have been lost and adrift without it.

3.2 Legal Status and Incorporation

In the 1960s, the Montreal Buddhist Church made an effort to gain a more independent and secure situation for its community by appealing for legal status. The church wanted to become incorporated so it could keep registers of births, marriages and funerals and exercize all the normal functions of other churches in Quebec—a right that Buddhist churches in other provinces can exercise. This, however, was problematic. On the one hand, the 1964 Quebec Freedom of Worship Act “grants: The free exercise and enjoyment of religious profession and worship, without discrimination or preference;” while on the other hand, the Quebec civil code says “that marriages and funerals must be solemnized by a ‘competent officer recognized by the law,’” which means only officers of Catholic, Protestant or Jewish faith (Watada 251-252). The Montreal Buddhist Church cannot perform civil ceremonies under this restriction. For a time a lawyer worked on getting these rights for the MBC, but dropped the case because he thought that it would threaten his career. There were several other ways to gain these rights, such as seeking a private act of the Quebec Legislature for incorporation, but members of the church saw this as being too complicated.

Then leader of the Buddhist Churches of Canada, Bishop Ishiura, saw the situation as a breach of the Freedom of Worship Act, and sought prominent individuals who thought likewise to help get things changed (Ibid.). Word got to American civil rights activist, Martin Luther King Jr., who offered to come to Montreal and march for the cause, but the church community thought such action would threaten their wellbeing and refused his offer. The church is still not incorporated.

3.3 The Late 60s to the Present: Ongoing Issues of Decline

The development of the major issues facing the church today can be followed from their origins in the late 1960s through to the present. While 1967 marks a new era of organizational facility and independence for Jodo Shinshu churches in Canada with the formation of the Buddhist Churches of Canada, it also marks a significant shift in the function of those churches. This has to do with the enormous changes in Canadian immigration law that took place that year. In October, the “points system was incorporated into the Immigration Regulations. The last element of racial discrimination was eliminated. The sponsored family class was reduced. Visitors were given the right to apply for immigrant status while in Canada” (Dench). In November, “The Immigration Appeal Board Act was passed, giving anyone ordered deported the right to appeal to the Immigration Appeal Board, on grounds of law or compassion” (Ibid.). While the effort to curb discrimination and encourage multiculturalism did not eradicate racism entirely, it is an indicator of the changing attitudes toward non-European ethnicities. For Japanese culture and Buddhism, this meant being viewed more idealistically and romantically by western eyes.

What all this meant for the MBC is that its function as an ethnic enclave preserving a national consciousness was lost, as sansei (children of nisei) do not share the experience that made it a necessary institution for issei and nisei. It was easier for sansei to become assimilated into Canadian society, and so they are less concerned about preserving a Japanese cultural identity and national consciousness. Moreover, the problem of not having many sansei members to keep the MBC alive is exacerbated by the fact that many of them do not stay in Montreal. I have spoken to numerous nisei members whose children have moved to Toronto or Vancouver because they do not speak French and had trouble finding work in Montreal. As their parents get older, they follow their children and membership declines. The issei members of the Montreal Buddhist Church have already moved away to follow their children who left for the same reasons as the sansei.

It is worth mentioning here that, while the MBC does not mean the same thing to sansei as it does to issei and nisei, it seems to mean something similar for another more recent demographic that has appeared since the interest in multiculturalism: the shinijusha (recent Japanese immigrants). Janet McLellan makes an observation about the Toronto Buddhist Church that is also appropriate in the case of the MBC:

For over fifty years Toronto Buddhist Church has functioned as an important element in maintaining and reaffirming the Japanese-Canadian ethnic identity based on a shared collective memory and values. It is precisely this ethnic identification that simultaneously alienates sansei and non-Japanese members and attracts shinijusha…. (66-67)

Several members of the MBC, including the current president, are shinijusha. The church is their closest link to Japanese culture in Canada. One even went so far as to say that Japanese communities in Canada are more Japanese than those living in Japan.

Membership has declined since its peak in the 1970s and continues to do so. When its membership was highest, the church had around 125 members. By the late 1980s this had decreased to about forty-five to fifty members, and remained that way through the 1990s. Currently there are about thirty to forty members, though only ten or so attend services regularly. Most members now are elderly nisei, many of them into their eighties.

As a result, the church no longer holds most of the community focused special events mentioned above. There is still a yearly bingo and spaghetti party in November, and karaoke on the first Saturday of every month. These, however, are organized by the Japanese Canadian Culture Center and not the church itself. One new activity has been created recently: for the past two years the current president has been giving Japanese lessons to two or three students every Friday night from 7:00-8:30.

Another consequence of the decline in membership is that the church has not been able to afford a full-time minister since the late 70s. Instead it has a lay leader from the congregation who conducts services, though he is not allowed to give a dharma talk as an ordained minister would (about which more in Ritual and Practices). Several times a year, ministers from the Toronto Buddhist Church come up to conduct services for special celebrations, and the BCC bishop comes once a year. This problem is not unique to the MBC. There are only eight ministers for the seventeen churches in Canada, and in order to deal with this issue, the current bishop of the BCC has started a lay leader training program so that lay practitioners can learn to conduct services in the absence of ministers.

Other churches, such as the Calgary Buddhist Temple, have dealt with the problem of declining membership by encouraging membership from outside the Japanese community. The Japanese United Church in Montreal has done likewise. While one MBC member with whom I spoke is eager for the church to be more active in its proselytizing, there does not seem to be a consensus within the community as to whether or not it should open its doors to non-Japanese members. As a non-Japanese visitor I was met with great enthusiasm and encouraged to return, though I felt no pressure to become a member.

| 4.0 Doctrine and Beliefs |

In this section I will first discuss the basic teachings of Shinran Shonin (1173-1262), the founder of the Japanese school of Pure Land Buddhism called Jodo Shinshu. Shinran “was a Japanese monk who rejected the monastic priesthood to teach that lay people could attain salvation by placing their faith in the power of Amida Buddha…” (McLellan 40). His ideas about faith and salvation are at the heart of Jodo Shinshu belief. The second part of this section will look at how and where Canadian Jodo Shinshu beliefs take these ideas.

4.1 The Foundation of Jodo Shinshu Buddhism: Shinran’s Pure Land Teachings

The bodhisattva Dharmakara made forty-eight vows that state the conditions under which alone he would attain buddhahood. The most important of these for Pure Land is the eighteenth:

May I not gain possession of perfect awakening if, once I have attained buddhahood, any among the throngs of living beings in the ten regions of the universe should single-mindedly desire to be reborn in my land with joy, with confidence, and gladness, and if they should bring to mind this aspiration for ten moments of thought and yet not gain rebirth there…. (Gomez 167)

The term “single-mindedly” is important here, I will return to it momentarily. First the issue of the condition without which Dharmakara will not attain perfect awakening needs to be addressed. This condition is very similar to the bodhisattva vow to not achieve buddhahood until all sentient beings do so: Dharmakara will not attain buddhahood until all living beings are born in his Pure Land. There is a catch though: “Finally, ten kalpas ago, he attained Buddhahood and is now dwelling in his Buddha field, the Land of Bliss, trillions of Buddha lands west of this world” (Ueda & Hirota 108). Dharmakara has become Amida Buddha, yet it seems as though all living beings have not been born in the Pure Land. There is an important paradox here: all living beings must have been reborn in the Pure Land because Dharmakara became Amida, but visibly this is not the case. An explanation for it can be found in Shinran’s doctrine of Other Power (tariki).

Jodo Shinshu practice is focused on chanting the nembutsu, which “consists of three words: namu Amida butsu: I place my faith in Amida Buddha” (McLellan 40). Shinran states “that only those who say the Name single-heartedly attain birth in the Pure Land of bliss; this is the meaning of ‘Those who say the Name all attain birth’” (453). This translation uses that term “single-heartedly,” but it means the same thing as “single-mindedly” referred to earlier. This means that one must say the Name with absolute faith in the power of Amida’s Vow—with a single mind, undivided between faith and doubt—in order to be born in the Pure Land. As Shinran states, “Faith is the heart and mind without doubt . . . To be free of self-power [jiriki], having entrusted oneself to the Other Power of the Primal Vow [of Amida]—this is faith alone” (451).

The idea of absolutely entrusting oneself to Other Power is key here. Hee-Sung Keel notes, “ . . . for Shinran faith is itself a gift from Amida; genuine faith cannot be the product of our impure and false minds, just as genuine practice of nembutsu can only be given by Amida as the Great Practice” (83). The reason for requiring Amida’s help is that because life on earth is so full of defilement, so clouded by samsara, that it is not possible to achieve enlightenment in it. Amida’s Pure Land, on the other hand, provides a setting much more conducive to the task; because earthly existence impedes humans from being born there of their own will, they must rely on the unclouded, enlightened power of Amida for that birth.

The reader will notice another paradox here that is related to the one discussed above: a practitioner must be the one chanting and having faith, but at the same time he cannot, by his own power, “single-mindedly” chant with true faith; this only comes as a gift from Amida—through Other Power. D.T. Suzuki explains this phenomenon, “We may think we are sincere and in possession of full faith or belief in Amida . . . but real faith, real sincerity is altogether devoid of such consciousness. As long as sincerity is conscious of itself, it is not genuine” (29). Later he writes,

When we are conscious of sincerity we are generally also conscious of insincerity, for they are mixed up with each other. When insincerity and sincerity are transcended, then Amida comes into our inner self and identifies himself with this self, or this self finds itself in Amida. (40)

Since Dharmakara has already become Amida, all living beings too have already been enlightened. To put it differently, the power of Amida’s enlightenment is within all living beings. Self-power and Other Power are identified yet remain opposed in that all beings contain the power of enlightenment within themselves, though it has been put there by Amida and not themselves. When someone utters the nembutsu with true faith and sincerity, the nembutsu is really uttered through him by the Other Power within him. To use Suzuki’s words again, “In fact, when other-power is embraced by self-power, self-power turns into other-power, or other-power takes up self-power altogether” (22). Other Power is the potential within living beings that cannot be activated by the ego, but arises without volition. Salvation involves a change in the way one perceives samsaric existence: one must recognize that Other Power is implicit in self-power and allow the former to manifest itself through the latter.

4.2.0 Formal Doctrine and Beliefs According the BCC Bishop

I was able to attend the first lay leader training session ever to be held in Montreal, led by the current BCC bishop. The lengthiest part of the training consisted of a classroom style lesson in the formal doctrine and beliefs of Jodo Shinshu Buddhism. The following section will explain the doctrine as learned there.

4.2.1 “What is Jodo Shinshu?”

The first and most important question to ask as a practitioner is “What is Jodo Shinshu?” While the official answer to the question of doctrine is that there is none—that the BCC and Nishi Hongwanji do not give doctrinal instructions, but leave that up to the individual—the threefold answer to “What is Jodo Shinshu?” comes in the imperative voice:

- listen to hongwanji

- recite nembutsu

- enter nirvana

Hongwanji here does not refer to the Nishi Hongwanji institution. It translates as “Primal Vow,” or “True Wish of the Buddha.” The reference here is to the eighteenth vow of Dharmakara discussed at length above.

Jodo Shinshu begins and ends with nembutsu—it is what Jodo Shinshu is all about. So the next important question to ask when trying to figure out what Jodo Shinshu is, is “What is namu Amida butsu?” It bears the same relationship to Jodo Shinshu as koans do to Zen Buddhism.

Namo can be translated as “go to,” “rely on,” “return,” “surrender myself.” Amida is a translation and combination of amitabha, meaning “infinite light,” and amitayus, meaning “infinite life.” Butsu means “Buddha.”

The name Amida is very important here. Light is a space notion, and life is a time notion. Without light one could not see space, and lifespan is a way of measuring time. Amida Buddha has two unique characteristics with respect to these dimensions: he is infinite and permanent time and infinite and permanent space. Amida is everywhere at every time—he is the entire universe, and we are living and dying within his embrace. The problem is that humans live a clouded samsaric existence driven by egos, and therefore cannot recognize Amida, though we are within him. At the end of our lives, however, we are reborn into the Pure Land and become united with Amida.[1]

According to Shinran, nembutsu is a calling to every one of us to “come as you are,” and not worry about anything else. Amida’s calling can be compared to the wishes of parents or grandparents: If you understand this you attain shinjin, which is the attainment of nirvana in this lifetime, being able to recognize the world as Amida, unclouded by the egoistic inhibitions of human existence. Upon achieving this, one can lead a life of appreciation and become an agent of Amida’s compassion.

4.2.2 Hell

In Jodo Shinshu belief, there is no hell. In the afterlife there is only the Pure Land, and therefore no possibility of hell there. Rather, hell is something that one creates in one’s own life. The Buddha teaches not to create your own hell, though people often do so by wrong actions, which plant bad karma.

4.3 Other Notes on Doctrine and Beliefs

Even if you strip away the Christian terminology and behaviour, Pure Land Buddhism bears a striking resemblance to Pauline Christianity, with its emphasis that salvation depends on faith alone rather than right actions. However, while this is important and makes Pure Land traditions unusual in the context of other forms of Buddhism, it is also founded on a characteristically Mahayana principle that should not be overlooked. This is the structure of simultaneous opposition and identity discussed above in relation to Self Power and Other Power. While this is not the place to conduct a thorough analysis of Pure Land Buddhism’s context in the Mahayana tradition, one example may be permitted.

The Changeless Nature, from the Cittamatra (Mind Only) tradition, talks about the notion of Buddha Nature. The idea is that all beings possess the nature of the Buddha, i.e. enlightenment, but do not appear to be enlightened because that nature is obscured by defilements and the accumulation of samsaric deeds (see Maitreya/Asanga 56 and Gampopa 50). This simultaneous opposition and identity of samsara and nirvana, defilement and enlightenment, within every person strongly resembles the idea that, because Dharmakara has already become enlightened all sentient beings carry the power of enlightenment, but cannot recognize it on account of their samsaric, ego driven existence. Other examples can be found in Madhyamaka and Yogacara schools, but the interested reader will have to examine those for him or herself (Braitstein 2003a, b & c).[2]

| 5.0 Ritual and Practices |

5.1 Schedule of Services

The MBC holds two services per month: the memorial service for the families of the late, usually held on the first Sunday of every month at 10:30 a.m., and the regular service held on the third or fourth Sunday of every month, also at 10:30 a.m., the occasion for which changes every month according to the Nishi Hongwanji sacred calendar:

Gantan'e (January 1) |

New Year's Day |

Goshoki Hoonko (January 16) |

Shinran Shonin Memorial Service |

| Nirvana Day (February 15) | Buddha's entering Nirvana |

| Spring Higan (March 20) | Spring equinox day |

Hanamatsuri (April 8) |

Buddha's birthday |

Gotan'e (May 21) |

Shinran Shonin's birthday |

Obon (July) |

Celebration of our ancestors |

| Autumn Higan (September 20) | Fall equinox day |

Eitaikyo (November) |

Perpetual memorial |

Bodhi Day (December 8) |

Enlightenment |

Joya'e (December 31) |

New Year's Eve |

(From the Buddhist Churches of Canada web site: http://www.bcc.ca) |

|

Though regular services are now held on the nearest Sunday to the appropriate date, in Canadian Buddhist temples before World War II, “[t]raditional Jodo Shinshu religious services were conducted in Japanese and observed on the appropriate day of the Japanese Buddhist calendar” (McLellan 43).

5.2.0 Ritual Space

The MBC building is a townhouse turned Buddhist church and would not be recognizable as a religious institution were its name not written above the front door (Fig. 1).

|

| Fig. 1 |

The main floor consists of one large room, which is the worship area, or hondo. Fig. 2 shows the front half of it. The congregation faces the shrine on the room’s west wall. While west is the direction of Amida’s Pure Land, I think that here the directional focus is less formal than pragmatic, as the room’s layout makes it the most practical direction to face. The room seats thirty-two people on chairs, twelve on the right, and twenty on the left. There is no division of men and women. This differs from Jodo Shinshu temples in Japan, where the congregation sits on the floor and men and women are separated (women sit on the left side of the room, men on the right). The service leaders are located at the congregation’s right during services: at the far right of Fig. 2 is the podium where the chairman stands; just to the left of that is a small cabinet and prayer bell where the minister or lay leader sits.

|

| Fig. 2 |

Also of note in Fig. 2 are three identical crests: one on the front of the chairman’s podium, one on the top panel of the shrine, and one on the front of the podium in front of the shrine that holds the incense and incense bowl (see Fig. 3 for better images of the latter two). This is the crest of the BCC. Each of the three crests here, as well as the relief carving of the nembutsu north of the main shrine along the west wall, were carved and donated by the MBC’s current lay leader.

|

| Fig. 3 |

At the centre of the main shrine (Fig. 3) is a scroll of the nembutsu written in Chinese characters. It is a replica of an original calligraphic work by Shinran. The nembutsu is seen as the embodiment of Amida and, as here, can be used in place of a statue of him. On either side of the scroll hangs a candle representing Amida’s infinite light.

Immediately in front of the scroll is an offering of rice, and on the shrine’s next level below the one where the rice is placed are two more food offerings, usually fruit and/or sweets. These offerings to Amida, except the rice, are distributed amongst the congregation for consumption after the service.

On either side of the shrine’s central chamber where the nembutsu is housed, two panels open up at diagonals to it. The panel pictured in Fig. 3 on the left is a painting of Rennyo Shonin, the eighth patriarch of Jodo Shinshu and a descendant of Shinran. In the 15th century, Rennyo translated Shinran’s Chinese texts and “composed plain language versions of Buddhist epistles….” He is largely responsible for the popularization of Jodo Shinshu through his encouragement of the building of temples and his determination “to teach Jodo Shinshu so that all people would be able to understand and accept the true doctrine” (Watada 7). The image of Rennyo is a permanent fixture in the shrine.

The image displayed on panel pictured to the right of the nembutsu changes depending on the occasion for the service. In Fig. 3 it contains the names of the deceased honoured in a memorial service. During the Hoonko service I attended on 30 January 2005, the Shinran Memorial Service, it displayed an image of Shinran very similar to that of Rennyo on the opposite panel.

The flowers and candle on the cabinet immediately in front of the main shrine are expressions of gratitude to Amida.

In the foreground of Fig. 3 is a podium that holds an incense bowl and a container of incense. This is a standard feature of Buddhist worship spaces. Incense is offered to Amida and ancestors at designated times before, during and after the service.

Moving to the left of the main shrine to the south wall, we encounter an electric organ (Fig. 4). This is one of the more markedly Christian features of the MBC. The precedent for this was set in 1918 by a Nishi Hongwanji Buddhist church in Hawaii (referred to above) that first used an organ in its services. The organ is common to Jodo Shinshu churches in Canada.

|

| Fig. 4 |

Following the southern wall, to the left of the organ, are hung portraits of the current Lord Abbot of the Nishi Hongwanji, His Eminence Monshu Koslin Ohtani and his wife (no image available for this and the next three images I will discuss due to glare in the photographs). Abbot Ohtani is the twenty-fourth generation descendant of Shinran. To the left of those portraits is a painting of Shinran’s wife, Eshinni. To the left of that is a series of illustrations of the Toronto Buddhist Church. The MBC is closely connected to the TBC because the latter shares ministers with the former and, due to the restrictions on the MBC’s keeping registers, many of its members go to the TBC to be married. Also, several of the MBC’s nisei members’ children have moved to Toronto and are members of the TBC. Finally, beside the images of the TBC is a painting of Shinran.

Along the north wall, to your right as you enter the main room, is a statue of Shinran as a young boy (Fig. 5). The young Shinran was ordained at age nine, and this statue represents him at that period in his life. The hand gesture he is making, which resembles a Christian prayer gesture, is not that but a gassho. The right hand represents the Buddha and the left hand symbolizes the self. The gesture is a symbolic identification of the self with Amida. The identity of the self with Amida is an important concept in Jodo Shinshu, and we have seen it before in the discussion of Self Power and Other power in chanting nembutsu, where they become identified when the latter takes over and becomes the former.

|  |

| Fig. 5 | Fig. 6 |

Moving west along the north wall, past the statue of young Shinran, are three statues of Amida (Fig. 6). The centre statue represents him standing, making a teaching mudra with his right hand and one of boon-granting with his left. In the small statue to the right in Fig. 6, he is presented in the lotus position, doing the teaching mudra again with his right hand, and a meditation mudra with this left. I have not been able to figure out for myself, nor find out the significance of the other statue pictured.

5.2.1 Other Notes on Ritual Space

The top floor of the building used to be where the MBC housed its ministers when it had any. It consists of an office, a bathroom, a kitchen (no longer in use) and two main rooms with the church’s book collections. The two main rooms are also used for MBC board meetings and Japanese lessons.

The basement consists of one main room about the same size as the hondo. Sometimes luncheons are held there. I attended one after the Hoonko service where Japanese food and beer was served. Unlike during services, the men and women sat separately at different tables. At a head table sat the president, visiting minister and a guest abbess from a local Zen centre. As well as an opportunity to socialise, this luncheon served as an opportunity to discuss issues pressing the MBC, such as the future of its congregation should it get too small to support the church. Such issues were discussed amongst the members as well as between the two clergy persons. Though it was my first time at the church, many members were frank about issues such as the MBC’s current dilemma of member decline, and open to relating their personal histories, including anecdotes about time spent in the internment camps.

5.3.0 Ritual Process

5.3.1 Ritual Specialists

As noted before, services are conducted either by a lay leader or minister. When a minister performs the service he or she dresses in a fuho (Fig. 7), a formal robe that varies in colour depending on his or her status as well as the occasion for the service. The fuho looks like a Protestant minister’s robe and may have been designed that way in the process of Jodo Shinshu’s process of westernization in the early twentieth century. The minister also wears a kesa, which hangs around his or her neck. It is sewn with an interlaced rice field patch pattern, a characteristically Buddhist design. Beside the Japanese connection, another function of the kesa’s patchwork design is to connect Jodo Shinshu with older traditions of Indian Buddhism in which monks could only wear robes patched together from pieces of clothing donated to them.

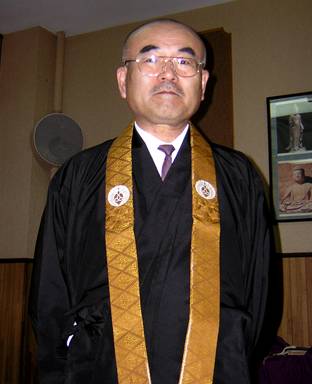

|

| Fig. 7: Bishop Orai Fujikawa wearing fuho and wa-gesa. |

While the lay leader dresses formally, usually with a shirt and tie, he does not wear a fuho. His only distinctly Jodo Shinshu article of clothing is a monto shikishou, which is a kind of simplified robe for lay practitioners that looks like a smaller version of the kesa. The chairman dresses similarly and also wears a monto shikishou during services.

The role of the chairman is to announce the beginning and end of every section of the service. Standing at the podium to the congregation’s right (see Fig. 2), he tells them when to stand up or sit down, which page to turn to in the prayer book, when to burn incense, and makes announcements once the service is finished.

The lay leader or minister sits behind and to the right of the chairman at a small cabinet with a prayer bell beside it (Fig. 8). From there he or she leads the congregation in meditation and chanting, ringing the prayer bell at the beginning and end of each chant or meditation period. The prayer bell is a standard Buddhist ritual implement.

If a minister is presiding, then he or she will stand up at the chairman’s podium to give a dharma talk towards the end of the service.

|

| Fig. 8 |

5.3.2 Ritual Objects

Jodo Shinshu practitioners are required to have three ritual objects:

- monto shikishou

- seiten

- nenju

The first is discussed in the previous section. The seiten is a prayer book. It looks like a Protestant prayer book, containing a creed, selected readings from scripture, Shinran’s letters, commentaries and gathas put to music that, when performed with the church organ accompanying, sound like Protestant hymns. It contains readings from the primary Jodo Shinshu sutras: the Smaller Sukhavativyuha sutra (in its entirety), and excerpts from the Larger Sukhavativyuha and Amitayur Dhyana sutras (McLellan 40). Much of the seiten is written in both English and Japanese. The sutras are written in old Chinese characters, with Japanese and Roman alphabet transliterations to assist in chanting. They are also translated in English. The gathas are mostly written in Japanese with Roman alphabet transliterations.

|

| Fig. 9 |

Nenju are prayer beads (Fig. 9), which are a standard Buddhist ritual object. Practitioners use these during meditation. A practitioner receives them after going through the sarana affirmation, at which point he also gets a Buddhist name and officially becomes a Jodo Shinshu practitioner.

5.3.3 Sequence of Events

Memorial services and regular services follow the same basic structure. The only significant difference is that different sutras and gathas are chanted and sung for regular services depending on the occasion. Services are conducted in alternating English and Japanese.

A service formally begins when the chairman announces that it is starting. The minister or lay leader then stands up and leads the congregation in reciting nembutsu, after which he sits down and begins the meditation period by ringing the prayer bell, and ends it the same way.

The next section is the Invocation, in which the Jodo Shinshu Pledge is recited from the seiten. This is followed by recitation of the ti-sarana, or Three Treasures: “I go to Buddha for guidance, I go to the dharma for guidance, I go to the sangha for guidance.” This can be done by the minister, lay leader or chairman.

The chairman then tells the congregation to stand up and a gatha is sung, usually the shinshu shuka, or “Shinshu Anthem,” which expresses gratitude to Amida. It is important to note that neither Amida nor ancestors are ever prayed to in the sense of asking them for something. Rather, Amida is thanked for guaranteeing rebirth in the Pure Land, and ancestors are thanked for preserving the dharma (they are all buddhas, since, as discussed above, Jodo Shinshu Buddhists believe that after death everyone is reborn in Amida’s Pure Land).

Next comes the chanting of the sanbujou, which is followed by a sutra. Sanbujou is a short, slow chant in which the congregation calls upon the buddhas in ten directions for spiritual guidance. This means calling upon one’s ancestors as well for reasons already discussed. After this a sutra is chanted in its entirety. These can be very long, though that depends on the occasion. At the Hoonko service the shoshinge, a gatha written by Shinran which takes up over twenty pages in the seiten, was chanted in its entirety instead of a sutra.

While the chanting goes on, the chairman stands up at his podium and calls for representatives either of the deceased’s families (if it is a memorial service), or from Montreal Buddhist societies (if it is a regular service) to burn incense. Representatives from the Montreal Buddhist Youth, Montreal Dana-Fujinkai (a women’s society), Montreal Sangha Society (a men’s society) and MBC are called up at this time. Incense burning is conducted by walking up to the incense bowl, bowing (raihai) from about an arm’s length away, stepping forward, putting incense from the container into the bowl, performing a gassho to the nembutsu in the main shrine, stepping back and bowing first to the nembutsu, then to the lay leader or minister.

This is followed by the singing of another gatha, which alternates depending on the occasion.

Following the gatha is the dharma talk, if a minister is conducting the service. If no minister is present, then the chairman reads a dharma talk or letter by a minister. The dharma talk can be as long or short as the minister chooses, though it usually lasts ten to fifteen minutes. It can also take the form of a discussion with the congregation (though I did not witness such a talk). The dharma talk usually consists of an anecdote from which the minister extracts a life lesson or teaching about Buddhism. At the Spring Higan service, for example, the bishop related a tanka jointly composed by a Zen master and Rennyo:

Sleeping and waking up,

Moving around and eating,

Sleeping and waking up.

Doing this this way,

Doing that that way.

He said that this expresses a quintessential Buddhist message about the importance of being attentive to our daily activities and doing them properly, rather than being distracted by thoughts of the future that often make us “do this that way and do that this way.” These informal, anecdotal and instructive talks resemble a Christian sermon and probably adopted that form as part of Jodo Shinshu’s process of Christianization in North America. In Japanese Jodo Shinshu services these talks are more formal and much longer, sometimes as long as two or three hours. It does not seem likely that a western congregation would sit comfortably through such a talk.

After that dharma talk a final gatha is sung, and the chairman and congregation make announcements if there are any. The service is then closed and those who did not get the opportunity to do so earlier are invited to burn incense.

5.4 Other Notes on Ritual Behaviour

Before and after the service, members mingle and chat informally, some in English, some in Japanese. The men wear suits and the women also dress formally. The atmosphere is like that of most Christian churches at this time, though with important differences (i.e. the Japanese crowd, language and incense burning).

During the lay leader training, the bishop gave a few pointers on proper conduct in the hondo. When in the hondo one is to act as though Amida, Shinran and Rennyo are really there. As an exemplary model he told the story of a minister who put a portable heater under a statue of Amida when the main heating was off in his hondo.

The first thing one should do when entering the hondo is bow. When bowing you should keep your chin down and not look up, as you are not supposed to see who you are bowing to. It is symbolic of complete trust (here in Amida), and it is rude to look up. After bowing and before taking your seat you should burn incense. After that, say “hello” to Amida. The best way to do this is to recite nembutsu. While some members perform some or all of these gestures when entering, they are not universally practiced or strictly enforced.

| 6.0 Closing Thoughts |

The Montreal Buddhist Church and Canadian Jodo Shinshu in general represent a unique niche of Buddhism in North America. Zen Buddhism came to North America by the efforts and interests of American scholars and enthusiasts. Around 1905, under the tutelage of her guest, the Japanese Zen master Soyen Shaku, one Mrs. Alexander Russell “became the first American to begin koan study” (Fields 169-70). In 1928, Zen master Sokatsu Shaku told his disciple Sokei-an, “Your message is for America…Return there!” (Fields 178-79). Before and after World War II, Zen was popularized by Japanese and American scholars such as D.T. Suzuki as well as the influence of trends in popular culture such as the Beat movement (Fields 195-224). In both North America and Japan, Zen was being recognized as something that could and ought to spread to other cultures. Tibetan Buddhism became popular in North America under similar circumstances, through the efforts of figures such as Deshung Rinpoche, Robert Thurman and Thomas Merton (see Fields 282-305).

The difficult situation that the MBC finds itself in today is largely a consequence of the fact that the experience and function of Jodo Shinshu in North America has been more or less the opposite of other Buddhist schools that migrated here in the twentieth century, such as Zen and Tibetan Buddhism. Where others were welcomed by and opened up to affluent North American culture, Jodo Shinshu was the focal point of an oppressed, alienated and far from wealthy demographic. Even its Christianization, paradoxically, was part of the effort to preserve a Japanese national consciousness. However, with this experience receding further from the present reality for Japanese Canadians and turning more and more into history, Jodo Shinshu temples and churches no longer need to function as the anchors of their communities’ social life and culture. If the Montreal Buddhist Church and others like it are to survive, they will have to shed the skin of their former functions and discover a new niche in North American society.

Notes

1It is worth noting here that this belief marks the primary difference between Japanese Jodo Shinshu other Pure Land schools:

Within Jodo Shinshu belief the attainment of the Pure Land is for all eternity, whereas in Vietnamese and Chinese Buddhist belief, Amitabha’s Pure Land is a temporary refuge for purification before returning to the round of birth and death. Jodo Shinshu Buddhists believe that this present life is the last. Because Amida Buddha promised to save everyone without exception, there is no need to be born again, thus ending the cycle of rebirth. (McLellan 40-41)

2Special thanks to Lara Braitstein, to whom I am greatly indebted in this section of the report for her lectures on Mahayana philosophy in the fall of 2003.

References

Books and Articles

Buddhist Churches of Canada Ministerial Association. Jodo Shinshu Seiten. Kyoto: Buddhist Churches of Canada, 1991.

Fields, Rick. How the Swans Came to the Lake: A Narrative History of Buddhism in America. 3rd ed. Boston & London: Shambhala, 1992.

Gampopa. Excerpt from The Jewel Ornament of Liberation. Trans. Khenpo Konchog Gyalsten Rinpoche. Ithaca: Snow Lion Publications, 1998. pp. 49-55.

Hunter, Louise H. Buddhism in Hawaii: Its Impact on a Yankee Community. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1971.

Maitreya/Asanga. From The Changeless Nature, verses 96-126. Trans. Kenneth Holmes and Katia Holmes. Eskdalemuir (Scotland): Karma Drubgyud Ling, 1985. pp. 61-74.

Keel, Hee-Sung. Understanding Shinran: A Dialogical Approach. Fremont: Asian Humanities Press, 1995.

McLellan, Janet. “Japanese Canadians and Toronto Buddhist Church.” Many Petals of the Lotus: Five Asian Buddhist Communities in Toronto. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999. 74-100.

Shinran. “Notes on ‘Essentials of Faith Alone.’” The Collected Works of Shinran, Vol. 1. Trans. Dennis Hirota, Hisai Inagaki, Michio Tokunaga, Ryushin Uryuzu. Kyoto: Jodo Shinshu Hongwanji-ha, 1997.

Suzuki, D.T. Shin Buddhism. New York: Harper & Row, 1970.

Ueda, Yoshifumi and Dennis Hirota. Shinran: An Introduction to His Thought. Kyoto: Hongwanji International Center, 1989.

Interviews

Informal conversations with members of the Montreal Buddhist Church on 30 Jan., 6 Feb., 6 March, and 27 March 2005.

Interview with Mr. Abe, 30 January 2005.

Conversation with Rev. Grant Ikuta, 30 January 2005.

Conversation with Mr. Suga, 27 March 2005.

Interview with Mr. Tsuzuki, 27 March 2005.

Conversation with Bishop Fujikawa, 27 March 2005.

Dharma Talks

Dharma talk on Shinran Shonin by Rev. Grant Ikuta, 30 January 2005.

Dharma talk on enlightenment and mindfulness by Bishop Fujikawa, 27 March 2005.

Websites

Buddhist Churches of Canada. http://www.bcc.ca/. 11 April 2005.

Calgary Buddhist Temple. http://www.calgary-buddhist.ab.ca/. 11 April 2005.

Dench, Janet. “A Hundred Years of Immigration to Canada: 1900-1999.” http://www.web.net/~ccr/history.html. 11 April 2005.

Other Sources

Braitstein, Lara. “Madhyamaka: Nagarjuna and the Prasangika Madhyamaka.” McGill University, Montreal. 23 September 2003a.

---. “Yogacara: Trisvabhava (Three-Natures).” McGill University, Montreal. 7 October 2003b.

---. “Tathagatagarbha: the Buddha Nature in Indian, Tibetan and East Asian contexts.” 9 October 2003c.

Montreal Buddhist Church Monthly Newsletters. January 1988-December 1990, January-December 1995, January-December 2000, January-December 2004.

Bishop Fujikawa’s “Lay Leader Training Program.” 27 March 2005.